Drone Interceptors vs. Drone Jammers & Spoofers

In the battle against rogue drones, no instrument is more widespread than the drone jammer. Though heavily regulated by world communications authorities, the practice of signal jamming has been around since long before contemporary drones took flight. Unsurprisingly, the instant drones started causing trouble, drone jammers went to market. Availability led to their ubiquity in the counter-drone business, as other mitigation tools — like drone interceptors — didn’t arrive until later.

But how do jammers contend with evolving drone technologies and invasion methods? And how do they compare to drone interceptors, which are poised to take the C-UAS crown? Does jamming still have a role to play in today’s industry landscape? This article, the second entry in our “Drone Interceptors Versus” series, aims to answer these questions.

Jamming Drone Signals: A Background

First, let’s lay down some context for the unaware. A drone jammer is a device that interrupts a drone’s ability to follow orders. At the moment, there are only two ways a drone can carry out instructions. One way is by receiving input straight from the pilot, who directs the drone with a remote control. The other is by following a scripted route uploaded before takeoff.

In both cases, the drone relies on some form of radio communication. If it’s flown by remote, the drone depends on its connection to the pilot. Most drone transceivers use the 1.2 GHz, 1.3 GHz, 2.4 GHz, or 5.8 GHz frequency bands. If it’s flying a preset route, then the drone depends on satellite navigation, which is also a radio technology. GPS (United States), GLONASS (Russia), GALILEO (Europe), and BeiDou (China) satellites operate between 1164 MHz and 1610 MHz.

You can tamper with a drone by exploiting the channels it needs to receive information, regardless of where that information comes from. Ostensibly, that’s what all drone signal jammers do. How they do it, not to mention how well, varies by type.

Above: Russia’s R-330ZH “Zhitel” is a high-power, vehicle-mounted jamming system that’s said to block all kinds of radio communication.

Above: Russia’s R-330ZH “Zhitel” is a high-power, vehicle-mounted jamming system that’s said to block all kinds of radio communication.

Types of Drone Jammers

Drone jammers come in lots of different shapes and sizes. At the top level, you have high-power jammers and portable jammers. There are jammers that disrupt RF (as in remote control), jammers that disrupt GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems, as in GPS and its foreign counterparts), and some that can do both. Getting even more specific, there are also “true” drone jammers and drone spoofers, which technically aren’t jammers at all. We’ll get to that, but let’s start at the top.

While more effective than portable ones, high-power drone jammers are as hazardous as their name implies. Broadcasting powerful, far-reaching noise in all directions, they’re able to completely saturate a wide range of frequencies including RF, GPS, and beyond. This makes it impossible for drones to approach, but also compromises everyday devices like cell phones, creating a communications dead zone. For this reason, high-power jamming is typically reserved for wartime use, and rarely sees deployment in places with civilians.

Portable drone jammers are different from their larger cousins in both form and function. Often called “drone jammer guns” or simply “drone guns,” most are designed as handheld “rifles” that jam locally, firing “streams” of radio waves directly at the target. This means they’re safer and much more suitable for inhabited areas. On the other hand, it also means these devices can be hard to put to practical use. More on that in a minute.

Above: Italian soldiers train with a portable drone jammer, commonly referred to as a “drone jammer gun” or simply “drone gun.”

Above: Italian soldiers train with a portable drone jammer, commonly referred to as a “drone jammer gun” or simply “drone gun.”

Being the more admissible choice, portable jammers have become quite popular, which has given rise to a new, arguably better execution of the same concept: the drone spoofer. Drone spoofers look, feel, and operate like other portable drone guns, except they don’t actually jam drones. Whereas jammers broadcast noise to make radio signals unintelligible, spoofers hijack radio signals to take control of drones, forcing them to stop. This is done by transmitting compatible signals with enough strength to replace the source. In other words, where a jammer overwhelms, a spoofer overrides.

As you can see, there’s no shortage of options here. Whether the drones you expect to face are RF-controlled or GPS-guided, you won’t have trouble finding a jammer or a spoofer made to counter them. Thing is, no matter what type of device you pick, the job won’t be as easy as “jam drone, go home.”

Today’s Impracticalities

To understand how jammers can be applied effectively, it’s important to know that all types of drone jammers come with caveats. The impracticality of high-power jammers needs no explanation. In 99% of scenarios, flooding a large region with jamming waves simply isn’t in the cards. Portable drone guns, which were developed to overcome this problem, are far more realistic. But they have limitations of their own.

The Human Component

The biggest by far comes down to the person holding the drone gun. It makes little difference whether they’re a teenage recruit, a veteran sniper, or Captain America. If a drone truly has malicious intent, a human stands almost no chance of reaching it in time. Not in an urban space, anyway.

Drones can invade from any point on the map. Smart operators fly them low and fast, use rooflines for cover, and are highly unpredictable. Even traveling by vehicle may not be quick enough to respond, especially in cities with busy streets. Without an aircraft’s mobility, ground personnel are at an extreme disadvantage.

Plus, there’s the issue of hitting a drone on the move, which is easier said than done. Getting a clear visual once is unlikely, and should the shooter miss, losing sight of it again is all but guaranteed. If the drone’s objective is known, defenders can form a garrison and wait for the drone to come to them. But this doesn’t ensure that someone will hit the thing. And once it’s that close, there’s no room left for mistakes.

Above: Contrary to popular belief, not all drones react to jamming in ways that are expected or desired.

Above: Contrary to popular belief, not all drones react to jamming in ways that are expected or desired.

The Drone’s Reaction

Probability aside, what happens if ground personnel successfully reach the target and are able to jam it? Many commercially available drones are programmed to descend when they lose the ability to navigate, which is exactly what happens when they’re subjected to jamming. Not all drones react this way, though.

Others hover in place until the connection comes back, in which case the jammer needs to stay active until someone sprays the drone with lead. Erratic movement is another possibility, and can easily lead to a crash. Drone spoofers offer better results than conventional jammers at this stage, since they put the drone’s actions in the defender’s hands. Of course, that depends on the spoofer’s compatibility with the present drone, which is never an absolute certainty.

Fixed-wing drones are a whole other challenge. They may be easier to see, since they don’t fly as low as VTOL quadcopters. But they’re a lot faster. To make matters worse, not a single one is designed to land when jammed. Sometimes, a fixed-wing drone will crash. More likely, it will fly straight until it’s out of jamming range. Then, it will simply turn around and finish its mission, unlike the ground team that tried to stop it.

All of these outcomes — preferred ones included — are dangerous if the drone is carrying a bomb.

Tomorrow’s Challenges

Although jamming technology will remain important in the foreseeable future, counter-drone operations will soon have to contend with challenges that jammers alone are not prepared for. Partly, this is because drones are getting smarter, and so are the criminals that purposely abuse them. The other reason is that jammers conflict with plans for future infrastructure, and their use — which is already prohibited in the United States and elsewhere — is bound to become harder to justify.

Drones are Going Cellular

Many of the latest drones operate on 5G cellular networks rather than traditional remote control frequencies, allowing for greater range and enhanced smartphone integration. This is expected to become the norm, which poses problems for drone jammers of all kinds.

Unlike the public radio frequencies reserved for RC toys and garage door openers, cellular frequencies are pervasive and highly essential. Jamming cell signals, regardless of scale, can have unintended consequences. The United States government prohibits the use of jammers specifically to avoid the risk of collateral damage, which is not insignificant. This isn’t to say that portable cellular jammers, similar to current portable drone guns, couldn’t be used safely. We think they could. However, the implications of using them would need to be considered carefully, much more than they are with devices used now.

A cell-based portable drone spoofer wouldn’t present any danger at all. At the same time, it would also be needless. While RF drones communicate point-to-point, 5G drones are TCP/IP devices connected to the internet. Rather than attempt to spoof one up close, it would make more sense to hack the drone with a MITM (man in the middle) attack. This can be done without any extra devices, from halfway across the world if need be.

Above: University students assemble a one-off ground drone with a single-board computer and parts that are easy to acquire.

Above: University students assemble a one-off ground drone with a single-board computer and parts that are easy to acquire.

DIY is On the Rise

With the exception of military UAVs, almost all hostile drone activity to date has been perpetrated with drones made by known manufacturers. Legitimate businesses like Parrot, Skydio, and others that sell drones to consumers have to abide by regulations put in place by the FCC and equivalent agencies. The radio frequencies used to control these drones are therefore restricted to certain bands, and these bands are what jammers exploit to counteract drones.

But what effect do jammers have on a drone that operates outside these bands? Unless you’re using a high-power jammer to block all radio frequencies, the answer is probably none. Thankfully, only a handful of these wildcards have appeared thus far. We know for a fact that more are coming, though. Soon. Because it’s already very easy to build one.

Homemade drones like this Raspberry Pi with rotors only scratch the surface of what’s possible for the 21st-century hobbyist. Some common, inexpensive parts, a little bit of coding know-how, and two or three weeks of determination are all it takes to build your own air-worthy machine. And you can run it at a radio frequency that’s completely unique, so long as you don’t mind breaking the law. A terrorist wouldn’t think twice.

Spoofers would have an even harder time with a custom-made drone, since the drone’s software would likely be custom, too. Drone spoofers that mimic GPS would still work, provided that the drone relies on GPS. Speaking of which…

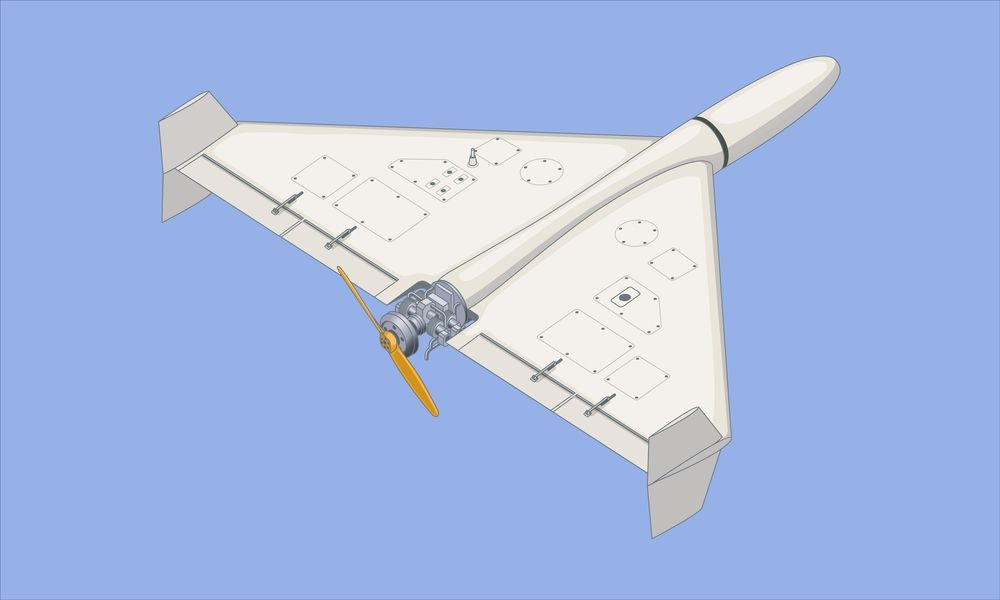

AI Can Substitute For GPS

As makers of autonomous drone interceptors, radars with microdoppler classification, and cameras with optical image recognition, we know a thing or two about AI. And we suspect the day when drones can fly themselves — without manual input or satellite guidance — is coming sooner than you think.

High-resolution optics are standard equipment for most drones, and some already possess the computing power to run sophisticated AI programs. Thanks to data giants like Google and Microsoft, the information needed to teach a drone to fly optically already exists in the public domain (think Google Maps). And drones have more than enough disk space to hold visual and geographical data that spans dozens, if not hundreds, of miles.

With emergent AI software, criminals will simply enter a destination and their drones will get there using onboard sensors and vision alone — no GPS required. As the technology matures, the usefulness of jammers and spoofers will be limited.

Above: Drones that can navigate using their optics don’t exist yet, but they’ll inevitably appear as artificial intelligence continues to improve.

Above: Drones that can navigate using their optics don’t exist yet, but they’ll inevitably appear as artificial intelligence continues to improve.

Infrastructure is Evolving

GPS jamming is already a risky business, and it doesn’t take a lot of thought to understand why. Worldwide, more than 15 million automobiles are equipped with navigation systems that drivers trust to get them where they’re going. Even more imperative are the nearly 10,000 airplanes flying overhead at any given time, which also rely on satellite guidance. The technology is even in our pockets — 15 billion cell phones that use GPS to geo-locate every day. And this is just the start.

Over the next few decades, the tech renaissance will continue, and the number of devices that connect to satellites will grow. Self-driving cars are a case in point. They’re already being made by various auto manufacturers, and it’s only a matter of time before they become the norm. Some people think even bigger. Several of the world’s largest companies are already invested in advanced air mobility, a vision of the future where people get around in autonomous, airborne taxis.

None of this will happen tomorrow, but all of it will happen. Progress will not stop for our industry’s convenience. As society’s dependence on GPS and other backbone radio technologies increases, the use of jammers, regardless of type, will be viewed as inadvisable.

Drone Interceptors Will Take Point

Getting back to the question at hand, how do jammers compare to drone interceptors?

Drone interceptors remove threats quickly, safely, and effectively, without creating radio interference. They take flight within seconds and race all the way to the edge of your detection dome, traveling at a constant speed and facing zero obstacles. Drone interceptors automatically adapt when a target changes direction and, if they happen to miss on the first attempt, they can chase the target until they successfully capture it.

By catching drones with nets, they leave nothing to chance, as a drone’s reaction is no longer a factor. Plus, the potential for collateral damage is far lower, since the invading drone is dealt with in mid-air. Response time is rapid because there are no bottlenecks. And, because interceptors are autonomous, there’s no chance of human error.

Jamming Strategies Will Transform

Without a doubt, drone interceptors can remove drones better than jammers can by themselves. By no means are jammers a thing of the past, though. Jammers, as well as spoofers, still have important roles to play in the days to come. The difference will be in the manner they’re used.

Rear-Line Duty

Like the saying goes, “don’t put all of your eggs in one basket.” Drone interceptors are superb drone-fighting machines, and should absolutely be the first line of defense for the world’s most critical C-UAS operations. That said, they should not be the only line of defense — at least not if you can help it. The best strategies in the business use a layered approach. In terms of detection, this means employing both radar and RF systems to maximize airspace awareness and intelligence. In terms of mitigation, it means using everything you’ve got to take down a hostile drone before someone gets hurt.

Sentries carrying portable jammers or spoofers can be an excellent second line of defense in the event your drone interceptor(s) fail to apprehend the target, however unlikely this may be. If jammers manage to slow a drone down, they can also make an interceptor’s job that much easier.

Jammer Interceptors

For that matter, jammers can even be attached to drone interceptors. Our DroneHunter® development team is engaged in joint research with partner companies that produce some of the best jammers on the market. We don’t expect to make any relevant announcements soon, but we’re confident that, if engineered properly, an airborne jammer could increase the F700’s already impressive capture rate.

Related posts